I’ve been exploring and researching this for months now on this blog, with the Future Trends Forum, on Twitter, with my Patreon supporters, through a series of interviews and webinars, and more. For today’s post, I’d like to build on that work to offer some scenarios for how higher education could develop by fall semester 2020.

The main driver shaping each one is three models of the pandemic itself. In late March I published a set of scenarios for how COVID-19 could play out. They included:

- The Hubei Model: A Single, Short Wave

- Viral Waves: Long Duration, Uneven Impacts

- The Long Plague

The titles are fairly explanatory. Each one differs in terms of length, shape, casualties, and overall impact. For more background you can read the post.

What might higher education look like in each different pandemic future? I suggest:

- The Post-Pandemic Campus

- COVID Fall

- Toggle Term

Caveats: in this post I am exploring future possibilities. I am not endorsing any particular analysis, political party, or course of action. I am also not assessing relative likelihood of these scenarios.

My primary target is United States academia, because of circumstances. Yet I think what follows can be applied to most nations, with some tweaking depending on local circumstances.

Each of these scenarios is a sketch. I try to cover as much institutional ground as I can, touching on curriculum, research, libraries, sports, etc. If you can think of an academic aspect I’ve missed – excellent! The comment box is yours. The idea of these scenarios is not to be the final word, but to spark thought.

I: POST-PANDEMIC CAMPUS

In fall 2020 the great pandemic has largely passed. Government after government has published figured showing infections and deaths dropping down to or below acceptable flu levels, after spikes and crises in springtime. Economies and civic life are rebounding as people increasingly return to face-to-face activities, albeit not to pre-COVID extent. It is a time of rebuilding and some reflection.

Colleges and universities have re-opened for in-person classes and research. The CDC has issued cautious guidance allowing this; state health authorities have published similar if varied notices. Students, staff, and faculty have returned, albeit in lower numbers than before.

The reason for those lower numbers is that some people are not wholly convinced COVID-19 has passed. Some do not trust various authorities: WHO, national governments, national health authorities, science, mass media.

Others are skeptical that campuses are safe. They point to conflicting scientific reports about the ability of the virus to life on physical surfaces. They worry about social networks, knowing well how readily students network with each other: stock figures here include Liberty University transfer students and the notorious spring breakers. They consider and share stories of coronavirus infections on campus or among campus populations in early 2020, as well as well intentioned acts like one college opening its residence halls to infected homeless people.

Colleges and universities – especially those with large residential student populations – go to great pains to assuage these concerns. They station expanded security forces around a perimeter, checking any person who would set foot within with forehead thermometers. Schools publish detailed accounts of how thoroughly they have cleaned every single campus space, from libraries to classrooms and especially dorms. They share safety certificates issued by various medical authorities. They maintain infection-tracking databases of each student, staff member, and professor, and do not publicize the contents or their conclusions. Some campuses publish detailed augmented reality content aimed at attracting tech-interested folks to return.

This is not entirely successful. Some students, staff, and faculty prefer to work from home (and there is a flurry of legal and policy action around this preference). The great migration online from February-May established that this could be done successfully, at least to a minimal baseline. As a result every campus activity simultaneously blends face-to-face with online presence. Each on-site seminar, lecture, staff meeting, interview, faculty senate, football game, theatrical performance, and presentation is paired with video screens, microphones, cameras, and text chat for remote participants. There is no settled name for this practice, but people try all kinds of terms: bimodal, blended, amphibious.

Research is similarly bimodal, as not all researchers and support staff are willing to return to labs and libraries. Resources are allocated differently than they were in 2019, as pandemic and recovery fields are deemed more urgent. Digital work of all kinds is on the rise, from telepresence manipulation to analyses of big data.

Pedagogy is more blended than ever, as a given class tends to contain a mix of in-person and remote students and faculty members. A wide range of pedagogical practices are in play, from asynchronous LMS discussion to live video discussion and virtual reality explorations. Some faculty work to expand their abilities in this hybrid space, while others fall back on pre-plague habits.

Enrollment in classes and majors has changed somewhat since 2019-2020. The full range of medical fields is more popular. Business and economics are even more popular than ever, given the needs of rebuilding nations. Political science and government enjoy larger enrollments given the extensive concerns about surveillance, governance, and geopolitics. Classes about COVID-19 or about pandemics in general see higher numbers, from history to literature and anthropology.

Some staff enjoy greater respect than they once held. IT, instructional design, and academic computing staff are quietly lionized for their heroic work. Librarians impress by their ability to work from within or beyond their building’s walls.

Depending on campus culture, some faculty members have become stars for their ability to teach in 2020’s new environment. Students and/or administrators may showcase them. Alternatively, or at the same time, some professors may be celebrated for their return to form in face-to-face class.

The combination of these changes means colleges and universities are suffering a financial hit as compared with calendar 2019. Springtime’s sudden migration online, refunds, deep cleaning, expanded security etc. all added costs. Overall enrollment is down (depending on the campus) and some discount their tuition, cutting revenue back. Institutions try all kinds of strategies to stay afloat: early retirements, flatlining professional development, hiring and/or firing adjuncts, increasing student workers, furloughs, cutting maintenance, suspending retirement payments. Academic program prioritization exercises and the occasional declaration of financial exigency enable administrations to remove tenure-track faculty. State governments urge some campus closures and/or mergers.

Liberal arts colleges welcome the change back to face to face experience, as they were often predisposed against remote instruction. Public universities struggle to balance drops in both enrollment and state support, then struggle to transform their curricula in a hurry. In contrast community colleges pivot rapidly to the pandemic curriculum; some enjoy rising enrollments where and when unemployment runs high. Some research universities are able to bank on their role in addressing the pandemic through R&D plus local medical support.

II: COVID FALL

In autumn 2020 COVID-19 still ravages nations. There is no sign of a vaccine on the horizon. No effective therapy has been devised beyond keeping infected people as comfortable as possible while their body struggles. New outbreaks occur worldwide. The total number of cases is upward of 500 million and the death toll stands somewhere between 1 and 4 million, although numbers are contested and variable. The global economy is in a depression, even including nations relatively free from the pandemic.

Nations and communities differ on how they are handling the pandemic politically, socially, and culturally. Some governments are heading towards collapse, unable to organize relief. Others are heading towards or have achieved authoritarian powers, conducting massive surveillance, and using both digital technologies and analog force to control their populations. Old and new religious movements have gained adherents, while science’s reputation sinks by the week.

Higher education is entirely online in this scenario. Classes, student life, research, and service all occur digitally. Orientation, Greek life, sports, glee club are online. So are advising, counseling, internships, and career placement. Paracurricular centers – writing labs, quantitative literary centers, research help, etc. – all have a digital presence.

Research is entirely online, with varied impacts depending on discipline and institutional type. Many humans find themselves thrown on which physical texts they have immediate access to, along with the digital world.

Pedagogies vary across institutions, academic units, and instructors. One school of thought calls for choosing technology based on student inequalities, so advises using asynchronous, low-bandwidth tools, including email, texting, mailed CDs and DVDs, along with print materials. Opposed to them is a practice based on using technology to maximize interpersonal presence. These faculty and support staff prefer synchronous and rich media experiences: high definition video, videoconferencing, virtual and extended reality. Between these two poles stretch a wide range of practices.

Post-secondary curriculum has changed significantly since winter 2019-2020. The pandemic drives the lion’s share of offered classes, majors, and enrollment. Medical, premed, allied health, and public health are at the center of most campus catalogs. Economics and politics follow closely, gaining as their respective fields of study degrade in the world. Some faculty members and department leaders in other fields strive to partake of this shift, offering classes, minors, majors, certificates, and courses of graduate study that link their intellectual domains to COVID-19: pandemic studies, anthropology of plagues, plague literature, epidemics in history, plagues in Italy then and now, etc.

In contrast, all other fields tend to shrink, partly due to students voting with their feet. Partly this is due to a powerful sense of national urgency, expressed through state governments, activist trustees, and a range of funders: grant agencies, foundations, philanthropic individuals, the most influential alumni.

A more powerful reason driving universities and colleges to rearrange their curricula is because most campuses are suffering badly from financial stresses. I’ve articulated the reasons for this previously. They include the many impacts on a campus from a generally rotten economy, higher costs from making the transition online, losses from lower enrollments, and possible tuition cuts. In emergency mode many colleges and universities will see pivoting to a COVID curriculum as a survival path. Other departments can experience personnel cuts, mergers with other departments, or being simply closed as this academic program prioritization proceeds.

because most campuses are suffering badly from financial stresses. I’ve articulated the reasons for this previously. They include the many impacts on a campus from a generally rotten economy, higher costs from making the transition online, losses from lower enrollments, and possible tuition cuts. In emergency mode many colleges and universities will see pivoting to a COVID curriculum as a survival path. Other departments can experience personnel cuts, mergers with other departments, or being simply closed as this academic program prioritization proceeds.

Colleges and universities will try other methods to raise funds. Given unused campus spaces, they may offer buildings for emergency purposes and for fees. Some may organize inter-campus collaborations to share resources of all kinds, from operational services to digital collections and classes. Enterprising campuses may offer their digital capacities to help other schools or organizations.

There may well be fewer colleges and universities by December 2020 as some see their economic viability dwindling. Mergers – which are really acquisitions – will be floated. Multi-campus systems and state governments can press for consolidations. Closures will occur.

Town-gown relations can be very stressed in this scenario. Rising dislike of science can play out with local resentment of scientific faculty. Economic crisis stokes jealousy in both directions. Cultural differences can become flashpoints.

Liberal arts colleges struggle with what they see as inferior or dematerialized instruction, and develop what they deem a uniquely liberal arts approach to the COVID fall term. Public universities struggle to survive; those with advanced online learning capacity are better positioned. Community colleges follow a similar pattern, depending on how much online teaching they can offer; some enjoy rising enrollments where and when unemployment runs high. Research universities focus attention on their role in addressing the pandemic through R&D plus providing some local medical support.

III: TOGGLE TERM

In this scenario fall 2020 is marked by rapidly succeeding viral waves. A country or region can be relatively free of COVID-19 for a time, then the pandemic roars back, driven by mutation or a new infection vector. Nations and cities toggle between states of lockdown and openness, depending on their sense of epidemiological data and practical feasibility. Economies are chaotic as market prices and supplies fluctuate.

Colleges and universities are now in perpetual crisis mode. Their leadership teams scan pandemic news minutely, aided by their medical faculty, looking for signs of when they can welcome their community back on site, and when to send them away and flip the switch to entirely online work.

Colleges and universities are now in perpetual crisis mode. Their leadership teams scan pandemic news minutely, aided by their medical faculty, looking for signs of when they can welcome their community back on site, and when to send them away and flip the switch to entirely online work.

Curricula have shifted towards the pandemic as in our previous two scenarios, but with a greater emphasis on organizational transformation and crisis management.

Classes now exist in a kind of double life, as faculty have created both online and face-to-face materials and plans for the entire semester. Lectures are prerecorded when possible, either for classic flipped classrooms or for remote instruction.

Campus services are similarly structured. Libraries, academic advising, mental health counseling, wellness centers, financial aid, bursars, work/study, career services and more are all ready to engage the community through in-person or on-line services.

IT departments work at a fever pitch. They must be ready to respond to very fast demands for changing delivery modes. Academic computing and instructional design staff work constantly with faculty to help maximize the pedagogical affordances of both modes.

Not all members of a campus community can toggle back and forth in their own lives. Some students decide to stay at home and engage remotely, while others manage to live on campus housing in quarantine circumstances. Some faculty and staff prefer to work from home. The end result by semester’s end is closer to the bimodal form we saw in scenario 1.

Toggling back and forth can be exhausting to all involved. Calls to pick one and stick with it will rise.

Town-gown relations are actually quite close in this scenario, as both entities experience the same toggle process. Universities and local authorities cooperate in this ongoing disaster management process.

Liberal arts colleges experience the toggle as a swap between two very different qualities of experience, preferring the in-person form. Public university systems pool resources and expand their collaborative planning, achieving something close to “systemness.” Community colleges focus their work on online teaching, but arrange syllabi to take advantage of in-person learning to do hands-on work. Research universities focus on what they discover in the medical world, as well as their analyses of organizational transformation in this extraordinary time.

What do you make of these scenarios? How do you see your institution or yourself in each one?

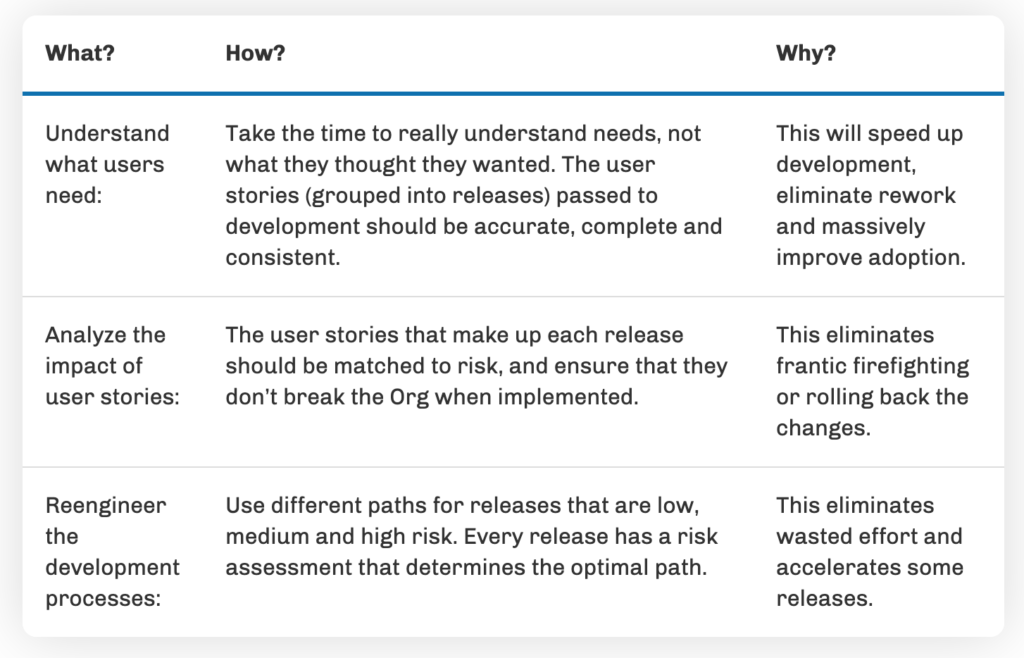

The more releases that can be taken through the low and medium development paths, the faster and more cheaply releases can be delivered. The development team is more effective. The business is more agile. Everyone wins.

The more releases that can be taken through the low and medium development paths, the faster and more cheaply releases can be delivered. The development team is more effective. The business is more agile. Everyone wins.

by

by

State funding for higher education

State funding for higher education

because most campuses are suffering badly from financial stresses. I’ve articulated the reasons for this

because most campuses are suffering badly from financial stresses. I’ve articulated the reasons for this