20 Ways Blockchain Will Transform (Okay, May Improve) Education

August 23, 2018 Leave a comment

Tom Vander Ark

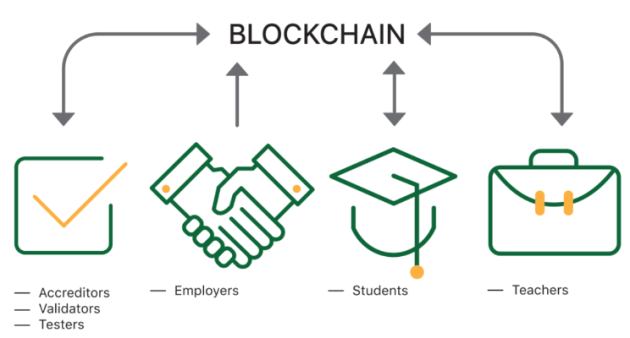

Blockchain is a public ledger that automatically records and verifies transactions. The distributed ledger technology (DLT) powers Bitcoin, Ethereum and other virtual currencies (which have taken a beating this month). Less publicized are all the ways DLT could transform many industries. Use cases for a transparent, verifiable register of transaction data are numerous because DLT operates through a decentralized platform making it fraud resistant.

With assistance from Educause and CB Insights, we’ve identified 26 ways that DLT could be deployed by school districts, networks, postsecondary institutions and community-based organizations to improve learning opportunities.

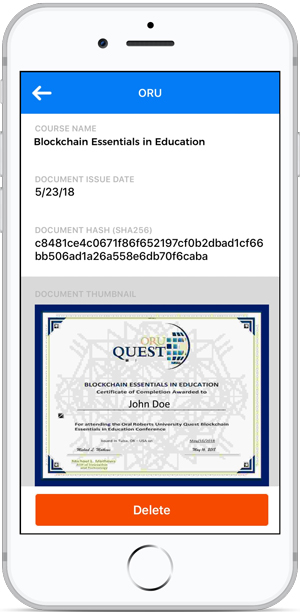

1. Transcripts. Academic credentials must be universally recognized and verifiable. In K-12 and postsecondary, verifying academic credentials remains largely a manual process (heavy on paper documentation and case-by-case checking). DLT solutions could streamline verification procedures and reduce fraudulent claims of unearned educational credits.

Learning Machine, a 10-year-old software startup, has collaborated with MIT Media Lab to launch of the Blockcerts toolset, which provides an open infrastructure for creating, issuing, viewing and verifying blockchain-based certificates.

Matt Pittinsky, CEO of transcript service Parchment, said there’s a lot of design decisions to work out before widespread use of DLT transcripts. He thinks blockchain will store locations to systems that that record comprehensive records–a balance between permanence and portability.

2. Badges. Specific skill assertions can be verified and communicated with a digital badge. Multiple badges can be assembled into an open badge passport that students can share with prospective employers.

Indorse is using blockchain to verify e-portfolios. Users upload claims with a link to verification and other users verify that claim.

3. Student records. Sony Global Education developed a educational platform in partnership with IBM that uses blockchain to secure and share student records.

Storing an comprehensive learner record on a distributed ledger may prove computationally intensive and, as a result, prohibitively expensive. As Pittinsky predicted, DLT may just be used as a directory rather than a data warehouse.

4. Identity. With the proliferation of learning apps and services, identity management is a big problem in education. Platforms like Blockstack and uPort help users carry their identity with around the internet. On Blockstack, users will access apps on decentralized networks and have data portability.

5. Infrastructure security. As schools add more security cameras and sensors, they need to protect their networks from hackers. Companies like Xage are using blockchain’s tamper-proof ledgers to sharing security data across device networks.

6. Ridesharing. Blockchain could inject new options into the rideshare oligopoly. With a distributed ledger, drivers and riders could create a more user-driven, value-oriented marketplace. DLT rideshare startup Arcade City allows drivers to establish their rates (taking a percentage of rider fares) with the blockchain logging all interactions. Arcade City appeals to professional drivers, who want to build up their own businesses than be controlled from a corporate headquarters.

School districts could negotiate with a group of screened Arcade City drivers for hard to serve aspects of pupil transportation (e.g., special needs, isolated students, work-based learning).

7.Cloud storage. As learners and education institutions store more data, DLT cloud storage could offer safer and potentially cheaper alternatives. Dubbed the “Airbnb for file storage,” Filecoin is a high-profile crypto project that rewards the hosting of files.

8. Energy management. For educational institutions with renewable energy sources, DLT could reduce the need for intermediaries. Brooklyn startup Transactive Grid enables decentralized energy generation schemes allowing entities to generate, buy, and sell energy to their neighbors.

9. Prepaid cards. Blockchains can help retailers offer secure gift cards and loyalty programs without a middleman. Gyft, an online platform for buying, sending, and redeeming gift cards, partnered with blockchain infrastructure provider Chain to run gift cards for thousands of small businesses on the blockchain, in a program called Gyft Block. Loyyal makes loyalty incentives easily exchangeable across different sectors.

Prepaid cards could be used by cities, schools, and families to purchase out of school learning experiences (e.g., an LRNG card) and associated transportation (#7).

10. Smart contracts. DLT can be used to automatically execute agreements once a set of specified conditions are met. These “smart contracts” have the potential to reduce paperwork in many sector including education.

Woolf University, formed by Oxford professors, will use DLT to execute smart contracts. A series of student and teacher “check-ins” are key to executing a series of smart contracts that validate attendance and assignment completion. A check-in could be a simple as clicking a button on a phone app but it executes a smart contract that pays the teacher and provides micro-credits to the student.

DLT could facilitate distributed learning skemes. A state or institution could fund a student’s account using blockchain-based smart contracts and and provide all the funding up-front. The smart contracts would release it when certain criteria are met. (There’s obviously a lot of policy to figure out: desirable experiences and skill verifications, eligible providers, terms and conditions, etc.)

11. Learning marketplace. The core competency of DLT is eliminating the middleman. It will be deployed to create various learning marketplaces from test prep to surfing school.

TeachMePlease is Russian pilot on the Disciplina platform where teachers and students come together. It helps students find and pay for courses, registered by educational organizations or teachers. Woolf (#16) is an example of a new higher ed marketplace.

12. Records management. DLT could reduce paper-based processes, minimize fraud, and increase accountability between authorities and those they serve. An early example, the Delaware Blockchain Initiative, aims to create an appropriate legal infrastructure for distributed ledger shares, to increase efficiency and speed of incorporation services. Illinois, Vermont, and other states have since announced similar initiatives. Startups are assisting in the effort as well: in Eastern Europe, the BitFury Group is currently working with the Georgian government to secure and track government records.

13. Retail. DLT could securely connect buyers and sellers in marketplaces.For example, OpenBazaar operates as an open-source, peer-to-peer network that connects buyers and sellers without a middleman. Customers purchase goods using any of 50 cryptocurrencies and sellers are paid in Bitcoin.

DLT could be used to power school stores and student businesses. In some cases, a global network would be attractive, but in others, a permissioned (private) ledger could limit the scope of a school economy.

14. Charity. For charitable donations, DLT provides the ability to precisely track donations and, in some cases, impact. For example, GiveTrack, from the BitGive Foundation, is a blockchain-based donation platform that provides the ability to transfer, track, and provide a permanent record of charitable financial transactions across the globe.

Donors to schools and NGOs may find accountability and transparency attractive.

15. Human resources. Conducting background checks and verifying employment histories can be time-consuming, highly manual tasks for HR professionals. If employment and criminal records were stored in DLT, HR professionals could streamline the vetting process and move hiring processes forward more quickly.

Chronobank is focused on improving short-term recruitment for on-demand jobs (e.g., cleaning, warehousing, e-commerce). The startup aims to use blockchain to make it easier for individuals to find work on the fly and be rewarded for their labor through a decentralized framework via cryptocurrency, without the involvement of traditional financial institutions.

Schools could use similar capabilities in substitute and driver management and for a marketplace of afterschool and summer activities.

16. Governance. The benefits of using blockchain for smart contracts and verifiable transactions can also be applied toward making business accounting more transparent. The Boardroom app, for example, provides a governance framework and app enabling companies to manage smart contracts on the public and permissioned Ethereum blockchains.

The app provides an administrative system for organizations to ensure smart contracts are executed according to rules encoded on the blockchain (or to update the rules themselves). Boards can also use the app for shareholder voting by proxy and collaborative proposal management.

17. Libraries. DLT could help libraries expand their services by building an enhanced metadata archive, developing a protocol for supporting community-based collections, and facilitating more effective management of digital rights. San Jose State’s School of Information received a $100K grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services to fund a year-long project exploring the potential of blockchain technology for information services.

18. Publishing. Blockchain could have multiple applications in the publishing industry, from breaking into the industry to rights management to piracy. New platforms are emerging to level the playing field for writers and encourage collaboration among authors, editors, translators, and publishers. Educators, students, and NGOs may appreciate the benefits of expanded publishing options.

Authorship allows writers to publish their work on the platform. Readers can purchase the books from the platform using Authorship Tokens (ATS), an Ethereum-based cryptocurrency, and writers get 90% of royalties in ATS. Authors own the copyright to their work, so they have the freedom to publish and distribute it elsewhere.

PageMajik is a workflow management system designed to streamline the publishing process. The system provides a secure, centralized catalog of all files, which can be easily accessed by teams of writers, editors, and publishers. Each person’s roles, rights, and duties can be specified before they actually start using the platform to minimize errors. PageMajik is in the process of adding blockchain technology to the next version of its workflow system.

19. Public assistance. Blockchain could help streamline public assistance system for families and students. The UK began working with startup GovCoin Systems in 2016 to conduct trials for developing a blockchain-based solution for welfare payments. GovCoin divides money into separate stashes for different expenses. Recipients gain access to their benefits which are paid in cryptocurrency via a mobile app.

20. Bonds. The World Bank is using blockchain to sell a bond. Moving the process to the blockchain could cut costs and speed up trading for both bond issuers and investors. School districts could benefit from faster and cheaper bond sales.

Writing for Educause, David McArthur outlines the limitations and challenges of DLT solutions in education. He also lays out the benefits Permissioned Distributed Ledgers rather than public ledger. These smaller private networks could enhance security and achieve faster and cheaper transactions consensus.

“When it comes to educational innovation, blockchains and ledgers are likely to lead to evolutionary gains, rather than revolutionary reforms,” concludes McArthur.

For more, see:

- Imagining a Blockchain University

- How Blockchain Will Transform Credentialing and Education (a review of an EU report on Blockchain in Education)

- By 2025, Swarms of Self-Driving Vehicles Will Transport Students to Learning Sites

Tom Vander Ark is an advocate for innovations in learning. As CEO of Getting Smart, he advises school districts, networks, foundations and learning organizations on the path forward. A prolific writer and speaker, Tom is author of “Getting Smart”; “Smart Cities That Work for (more) Read more of this post